EPI blog: No room for battle of the sexes: Why boys AND girls matter

|

In recent years, public debates on gender have increasingly focused

on boys and men falling behind. Data from Western countries

consistently show long-term gaps in educational attainment,

university enrolment, and degree outcomes. Boys are behind girls on

every official child development measure on starting school, and

continue to trail girls' attainment (on headline measures) as they

progress through compulsory education. Research highlights the

broader consequences,...Request free

trial

In recent years, public debates on gender have increasingly focused on boys and men falling behind. Data from Western countries consistently show long-term gaps in educational attainment, university enrolment, and degree outcomes. Boys are behind girls on every official child development measure on starting school, and continue to trail girls' attainment (on headline measures) as they progress through compulsory education. Research highlights the broader consequences, including declining marriage rates and poorer adult health outcomes for men. Yet some recent studies suggest that the trend of boys falling behind girls might be in reverse. EPI's recent annual report shows that, in England, boys are catching up with girls in GCSE English and maths, with the gap narrowing to 4.5 months in 2023, the smallest gap since 2011. Interestingly, we find that it is since the onset of the Covid 19 pandemic that the gender gap has shrunk the most: between 2019 and 2023, the GCSE gap markedly narrowed by more than three months.[1] This reduction in the gap is one of the biggest post-pandemic reductions across all of the attainment gaps that we considered. This reflects not only boys catching up but girls' performance declining in absolute terms. Separate studies also find that learning loss during the pandemic affected girls more than boys and international research shows boys are pulling ahead once again in maths and science. It's too early to tell if these findings indicate a long-term reversal of the trend we've seen over the last decade — but they raise the question: how worried should we be about girls? Girls' outperformance of boys in education has perhaps masked the emergence of other concerning trends, primarily their worsening mental health and wellbeing. As we explore in the section below, several indicators suggest the wellbeing of girls is deteriorating. This raises the question of whether these relatively poor wellbeing trends are now having an impact on girls' educational outcomes too? How have indicators of girls' and boys' wellbeing changed in recent years? We'll focus on data covering three broad areas of wellbeing, drawing on a range of data sources. The first area is mental health:

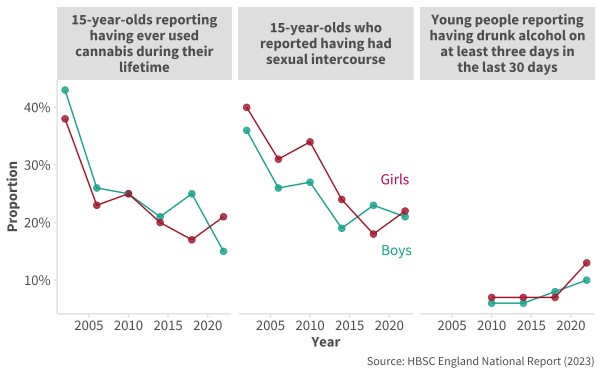

Figure 1: Gender differences in reported risk-taking behaviour

The second area is social media:

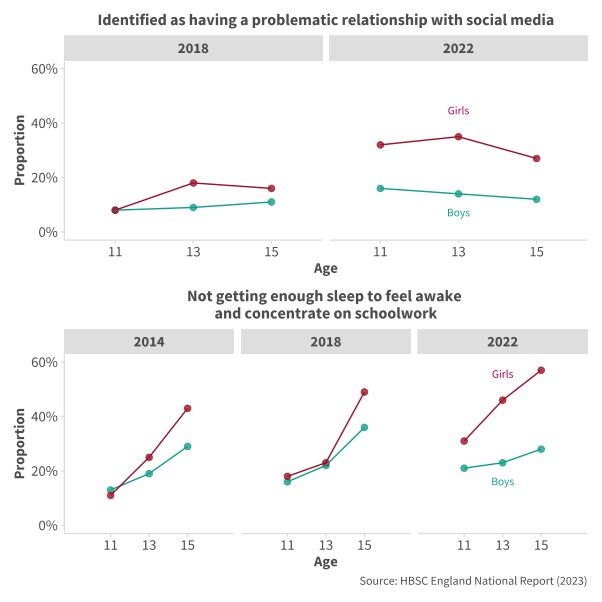

Figure 2: Gender differences in the proportion of young people identified as having problematic social media use and reporting insufficient sleep

The third area is safety and belonging:

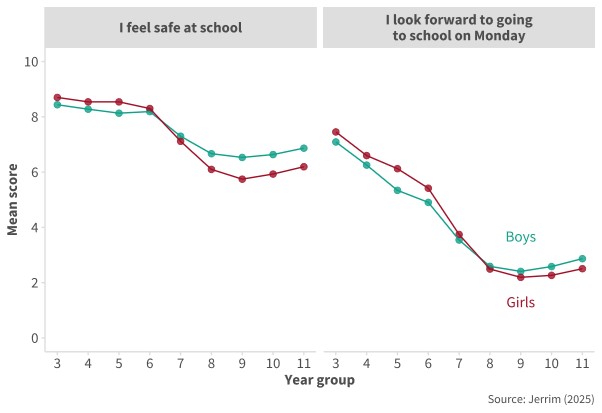

Figure 3: Gender differences in reported sense of safety and worry

We don't know why girls are now performing worse on a range of measures compared both with previous years and, in some cases, with boys. But one experience seems particularly relevant to explore given the current national conversation: the issue of violence against women and girls (VAWG). VAWG is any harm directed toward a girl or woman because of their gender. It lies on a spectrum, with behaviours ranging from harassment and intimidation to acts including sexual assault and exploitation. Violence against women and girls and their worsening wellbeing The few prevalence studies which exist show that sexual harassment and certain kinds of violence are common experiences for girls; in education settings these experiences are often dismissed or made invisible by their normalisation:

The Women and Equalities Committee highlighted the prevalence data in a 2016 inquiry and concluded that sexual harassment and abuse of girls is accepted as part of daily life in schools and colleges. These studies, spanning the last decade plus, show these experiences are not new — but the rise of digital technologies and social media over this period has opened up new avenues for abuse. For example, many young people are in constant unsupervised communication with peers and pictures are taken and shared more easily. And there is growing concern in the UK and US about online misogynistic content — backed up by some worrying survey findings on how its consumption is playing out in schools. In 2021, Ofsted published a review off the back of the Everyone's Invited campaign, an online collection of testimonies from young people from close to 3,000 schools in the UK and Ireland which highlighted experiences of sexual harassment, coercion and assault in or around school. The review found that virtually all girls interviewed had been sent explicit pictures or videos they did not want to see, compared with half of boys, and experienced sexist name-calling, compared with three quarter of boys. Authors concluded that these issues were so widespread that all schools and colleges should act as though sexual harassment and online sexual abuse are happening even in the absence of specific reports. The Department for Education responded by publishing updated guidance for schools and colleges on how to identify, minimise risk and respond to instances of sexual harassment or violence, which was later merged with broader statutory safeguarding guidance. Young people who experience gender-based violence may go on to struggle with depression, anxiety, eating disorders, substance misuse, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Given the high likelihood that many girls will experience some form of gender-based violence during adolescence coupled with the recent rise of online misogyny, we urgently need more research exploring how these factors may be driving the worsening mental health and wellbeing of girls. From surveys of young people and diagnostic prevalence data, we know that the gender gap in mental health emerges in early adolescence – at the same age when experiences of violence against women and girls in school and online likely become more common. What next? This blog lays out findings related to girls' and young women's wellbeing – on worsening mental health and related outcomes, and the high prevalence of VAWG. We find that across multiple indicators spanning mental health, social media use, and school safety and belonging, girls are faring worse than boys, and increasingly so, post-pandemic. It appears that narrowing attainment gaps may be symptomatic of the widening wellbeing gaps, but the reality is that robust research into how these factors interrelate does not yet exist. It's important to note that the education and longer-term outcomes of boys and girls still paint a complex picture. While the attainment gender gap may be closing (and in the case of maths and science, going into reverse), girls are still performing better than boys, on average. Yet, despite this, men continue to earn more than women particularly after early adulthood and the ‘motherhood penalty'. Taken together, existing research suggests that gender remains one of the most important factors for experiences and outcomes in education. More research is needed, addressing questions such as: do experiences of gender-based violence in schools and online play a role in girls' worsening mental health? Does exposure to online misogynistic content contribute to these experiences? And is there a pathway through which these potentially related factors are contributing to lower levels of belonging and safety, and worse attainment, for girls at school? We need a much stronger focus on pupil wellbeing, not just attainment outcomes, and, as a first step, to consider collecting this data centrally building on the work of the #BeeWell programme. How do we ensure all young people, regardless of gender, feel safe, respected and valued at school? How do we make education a place where they want to be and succeed? These are the urgent policy questions we must address. [1] This is after controlling for other pupil, school and region characteristics. |