Britain’s restrictive planning system and occupational

licensing rules hurt the worst-off.

-

House prices could be over one-third lower without

restrictive planning rules.

-

Almost 1-in-5 British workers are required to get a licence

to do a job, known as occupational licensing. This is up from

14% in 2008 and higher than in countries with high income

mobility, such as Denmark (14%), Sweden (15%) and Finland

(17%).

-

UK income mobility is “not exceptional in any way – neither

good nor bad” in international comparisons but could be

improved through economic liberalisation.

Britain’s poorest are being held back by restrictive planning

laws and labour market regulations, according to new research from the free

market think tank the Institute of Economic Affairs. Income

mobility in Britain has fallen since the 1970s at the same time

as housing and labour regulations have increased.

The authors, academics Dr Justin Callais and Dr Vincent Geloso,

say that the inability to build homes near better paying jobs

prevents social mobility. They cite US evidence that shows

households could be hundreds of thousands of pounds better off

over their lifetimes if they could move to areas that offer more

job opportunities.

Planning restrictions disproportionately benefit existing wealthy

homeowners, who can pass the gains of high house prices down to

the next generation. These restrictions have also increased

housing costs significantly. They cite research estimating that

in the absence of regulatory barriers, house prices in the 2000s

would have been 35% lower than they actually were*.

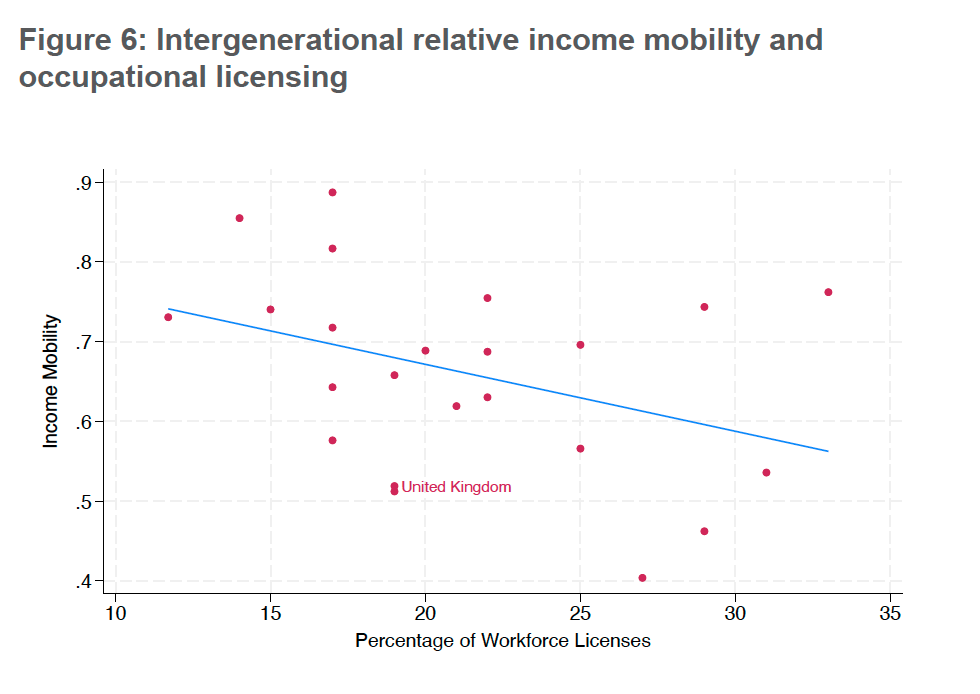

The authors say that Britain's least well-off are held back by

cumbersome requirements to get a licence for a growing number of

jobs. They calculate that if Britain were to bring workplace

occupational licensing regulation down to Danish levels, it could

boost income mobility by up to 1.6%. Returning UK labour market

regulations to 1990s levels, which would mean halving the number

of occupations that require a licence, could boost income

mobility by up to 3.1%.

The paper rejects the idea that increased government spending on

welfare and education is the best way to improve social mobility.

They highlight that more spending means higher taxation and lower

growth, entrepreneurship, and opportunity. Instead, Callais and

Geloso demonstrate that removing legal hurdles to work is the

most effective way to help the worst off in society.

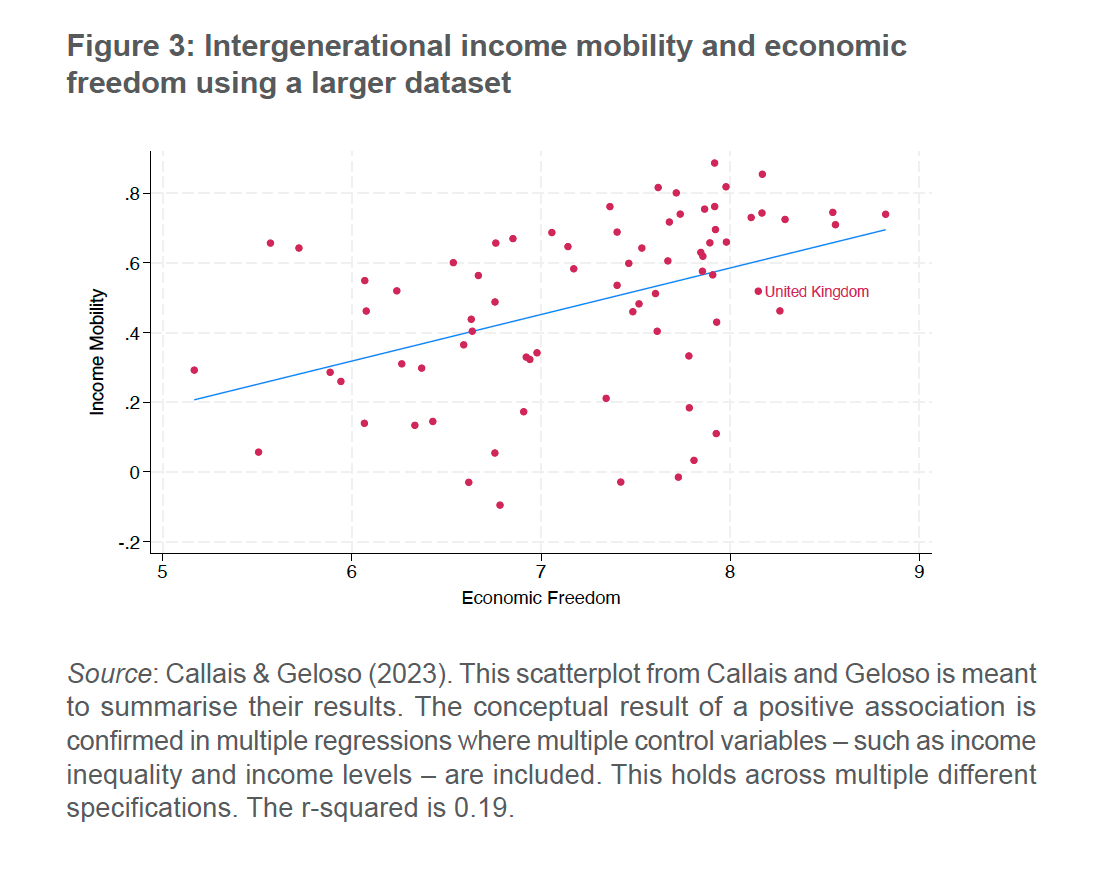

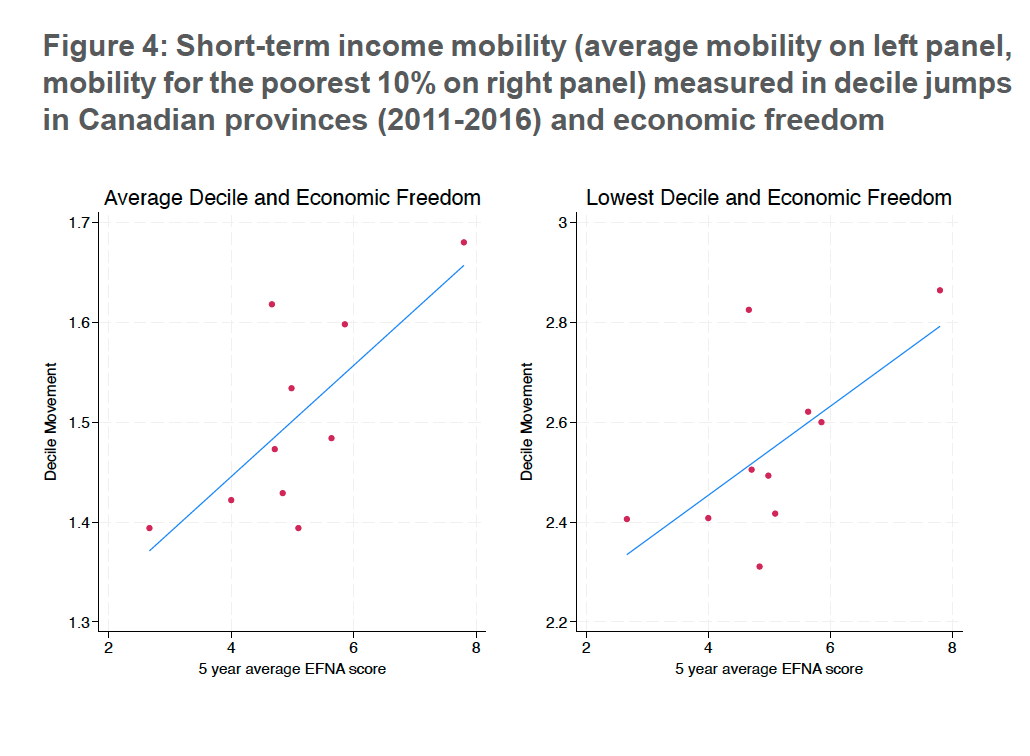

The authors cite extensive evidence demonstrating a strong link

between income mobility and economic freedom. “Limited business

and land-use regulation, more flexible labour markets, fewer

barriers to business formation, and more open trade can do more

to boost income mobility than is commonly appreciated,” Callais

and Geloso write.

Justin Callais, paper co-author and Assistant Professor

of Economics and Finance, University of Louisiana at Lafayette,

said:

“By focusing solely on inequality as the main cause of income

mobility, we are missing out on an even more important factor:

economic freedom. Economic freedom empowers individuals to excel

in their unique strengths, unlocking a vast array of pathways to

prosperity.

“Economic freedom has far fewer drawbacks than other proposed

policies like tax and redistribution, which lowers the returns to

productive activity. The British government would be wise to

consider robust changes to its policies on occupational licensing

and housing regulations in order to tackle income mobility.”

ENDS

Notes to Editors

-

*Hilber, C. A., & Vermeulen, W. (2016) The impact of

supply constraints on house prices in England. The Economic

Journal, 126(591), 358-405.

-

Absolute income mobility refers to increased living standards

throughout a person’s lifetime. Relative or intergenerational

income mobility is the difference between a person’s income

and others (for example, their parents).

-

Economic freedom refers to limited government and regulation,

safe and secure property rights, open trade and sound money.

-

Callais and Geloso have established a robust positive

correlation between relative income mobility and economic

freedom measures: